The Owlets have been busy learning all about California through a joyful, hands-on mini-inquiry inspired by curiosity, creativity, and discovery. Their exploration began in early January with a classroom art project focused on California poppies. After closely studying photos of the state flower and noticing its bright orange and yellow colors, the Owlets used liquid watercolors to create their own vibrant poppies. Although poppies typically bloom in the spring, they bloomed early in the Owlet classroom!

The inquiry officially began with the book Welcome to California, which introduced students to the basics of the state and continued to serve as a reference throughout the project. The Owlets eagerly shared places they have visited across California and quickly realized just how diverse the state’s landscapes are. To bring this learning to life, they worked together to create a large map of California, discovering coastal beaches, farmland, snowy mountains, forests, and deserts along the way.

In small groups, the Owlets used a variety of materials to represent where each landscape is located on the map. They also examined real photos shared by Owlet families and practiced matching each image to the correct region.

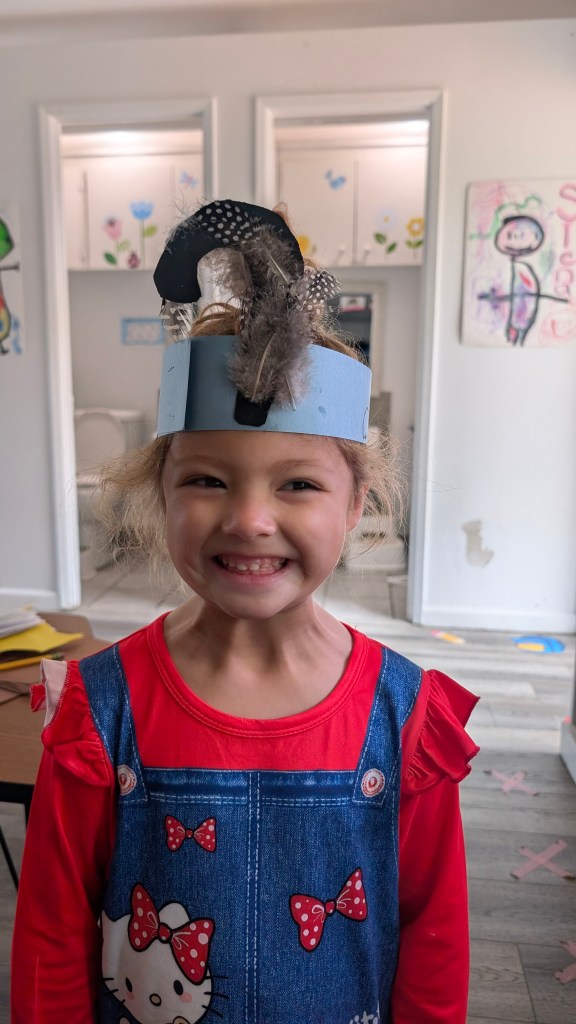

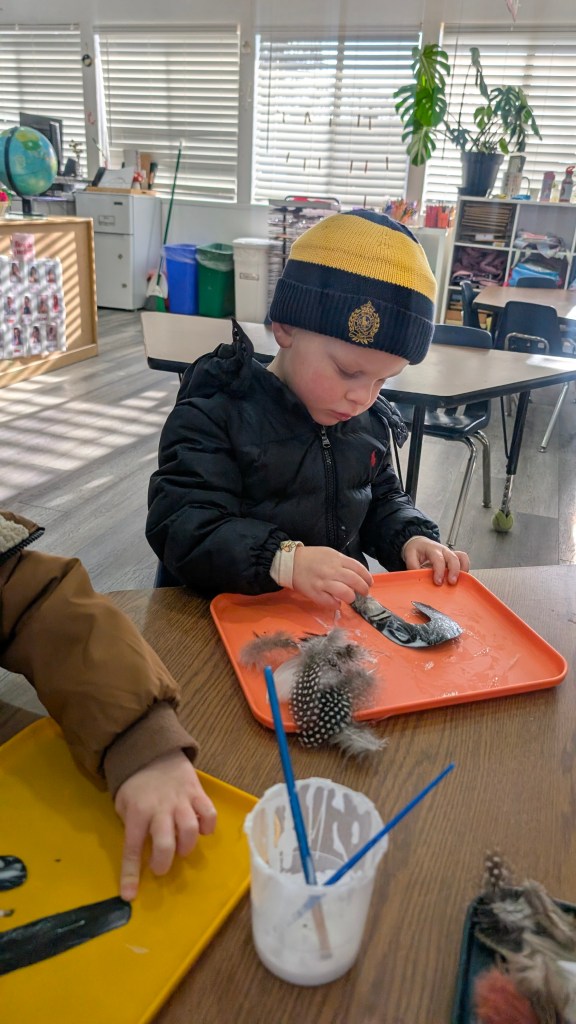

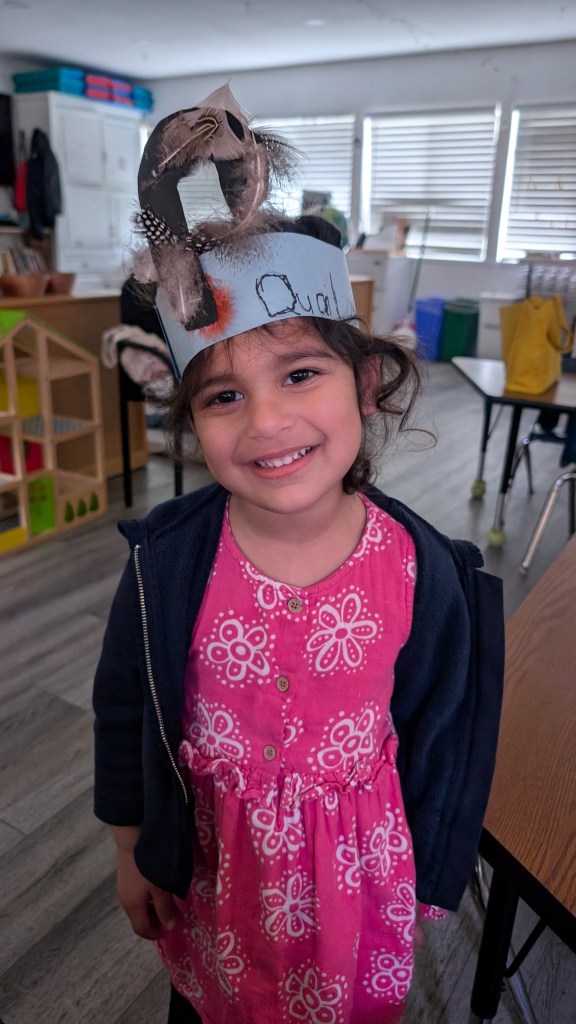

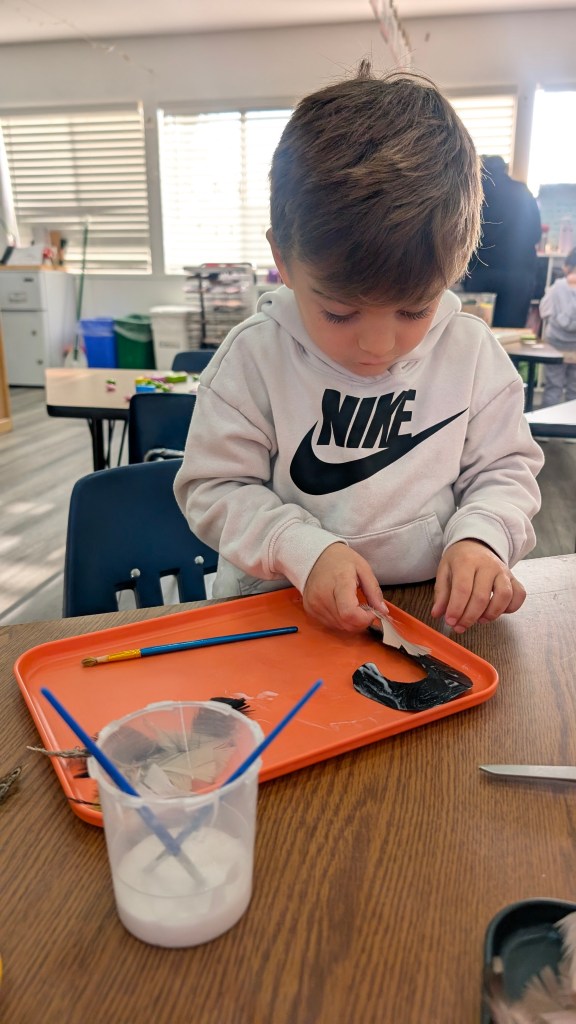

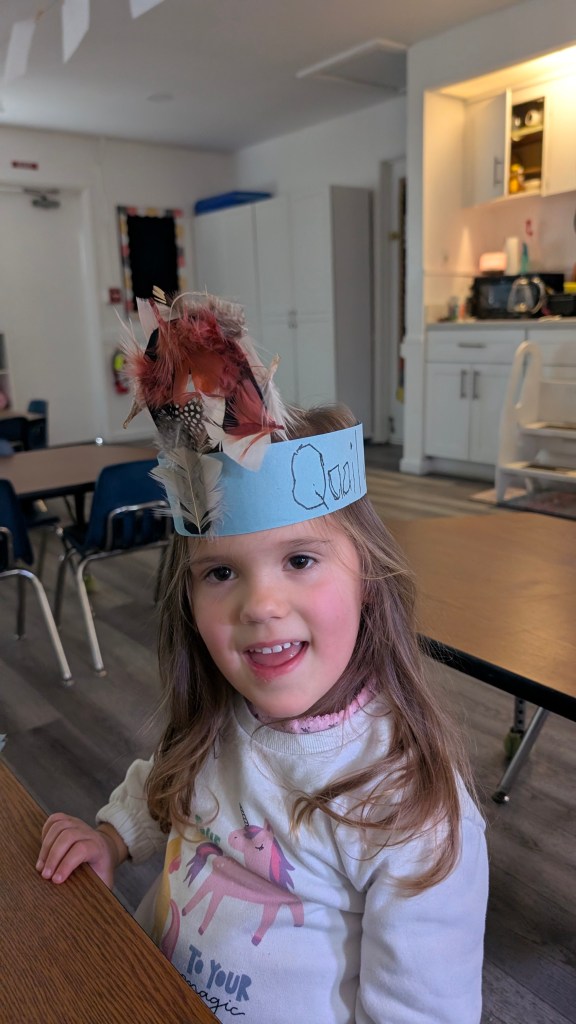

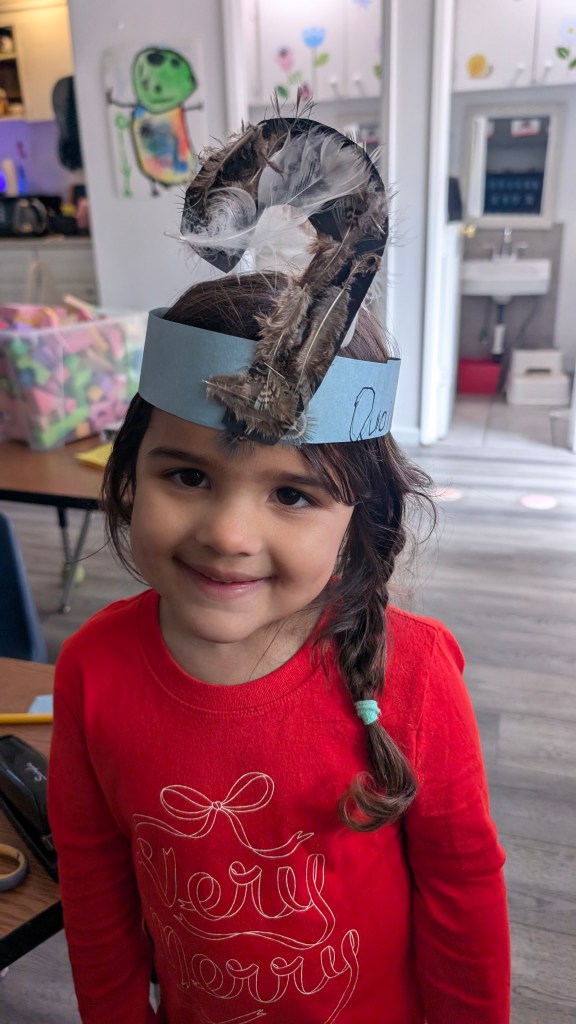

The Owlets also learned about California’s weather patterns and the animals that live in each region. They noticed that the desert is hot and home to animals that wouldn’t survive in cooler mountain climates. While studying the California state flag, they spotted the large brown grizzly bear and learned that grizzly bears no longer live in the state. This led to an exploration of animals that currently call California home, including black bears, foxes, coyotes, mountain lions, bobcats, and quails. Students were especially excited to discover a few “hidden” quails right in their classroom.

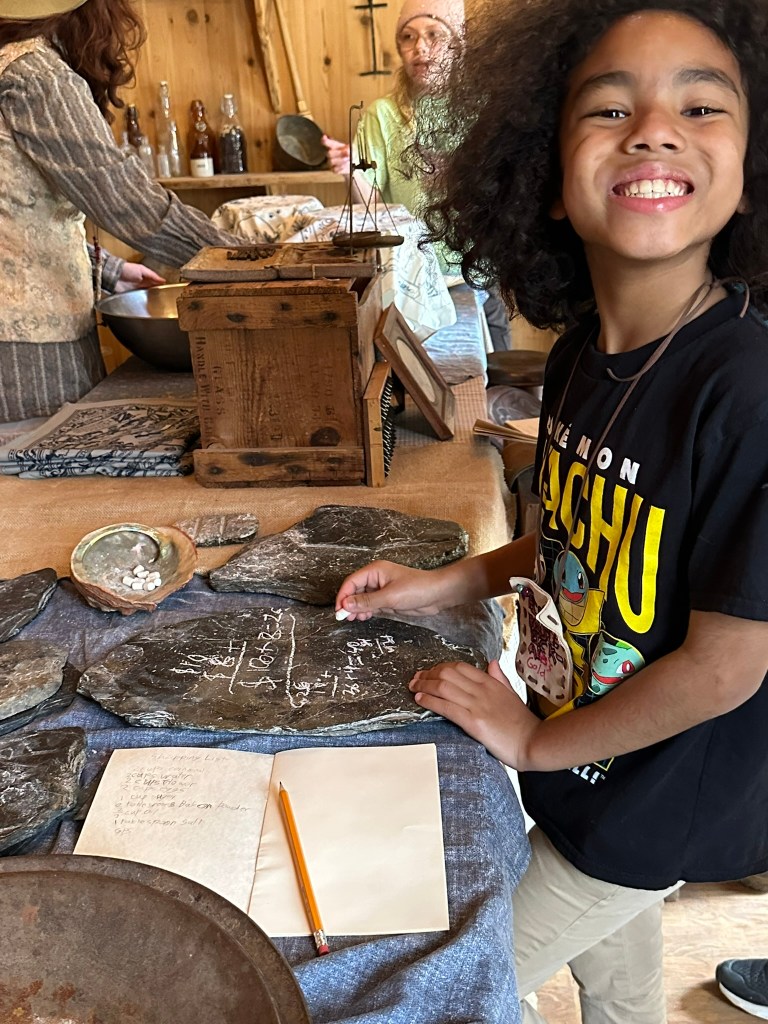

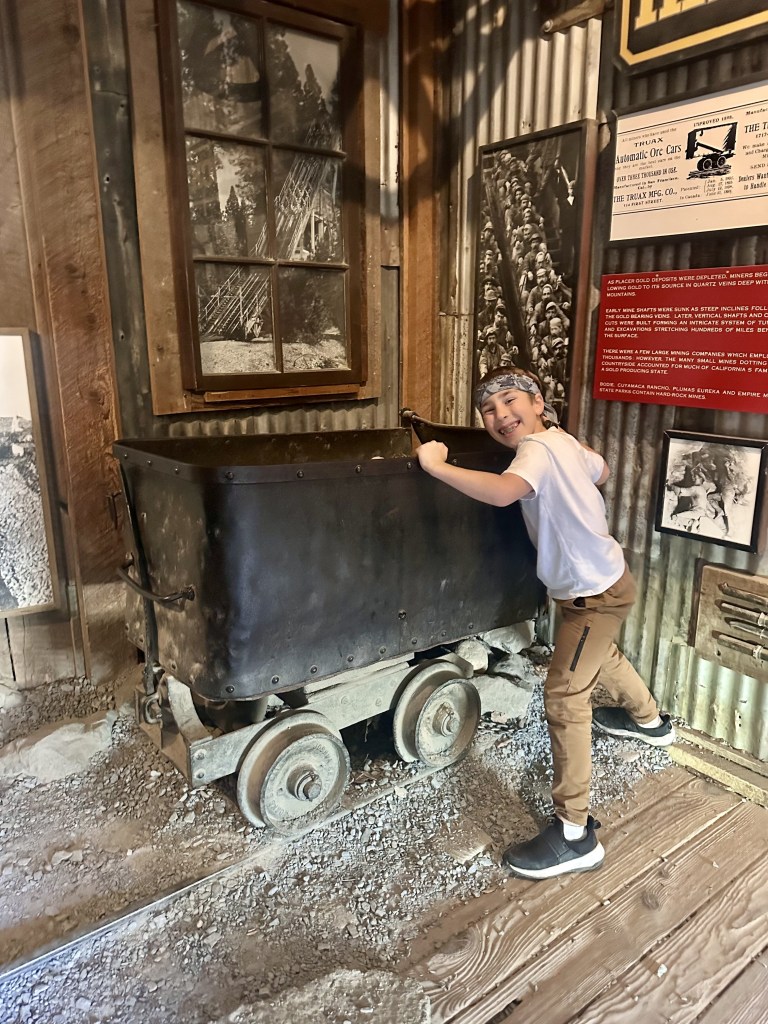

The inquiry wrapped in elements of California history as well, including a discussion of the Gold Rush and how people once traveled to the state in search of gold. Through art, literature, mapping, and imaginative play, the Owlets have built a strong foundation of knowledge about California—its landscapes, animals, symbols, and history—while nurturing curiosity and a love of learning along the way.

#SaklanHandsOn

You must be logged in to post a comment.